STEINKJERPOSITIVES

Digital museum for the Steinkjerpositives

the instrumentmakers and the positives universal appeal.

The "Steinkjerpositiv" is a barrel organ produced in the area of Steinkjer in Norway. European barrel organs from the same period as the Steinkjerpositives were usually more lightweight and were easier to carry. The Steinkjerpositives, especially the two larger versions were more like portable organs by comparison. The build quality for the instruments was comparable to all instruments from the era, and this is why so many have survived till today. Because of the great number produced, the Steinkjer positives have become a standard in Norwegian barrel organ traditions, and the name "Steinkjerpositiv" was more or less the established name on all mechanical organs built in Norway at the time. Around 600 positives were built between 1850 and 1910 in Steinkjer.

How could such a large

instrument production occur in Steinkjer?

It is well documented that many foreign travelers with barrel organs had been visiting the middle part of Norway from 1829. The travelers came first to Levanger where a market was arranged in December and March. From there they went on to Steinkjer with their instruments.

The picture is from the Levanger market, and originates from the collection of Harald Renbjør, Levanger Fotomuseum.In Beitstad an Italian barrel organ player passed away, and instrument maker Thomas Fosnæs studied his instrument. It has been said that this incident was the one which formed the idea in his mind that he could start making his own positives from around 1850.

But it turns out that Thomas had already started making barrel organs before this incident, but it may well be that travelers needed repair and maintenance of their organs, seeking his help as a watchmaker and a musician. And that was probably the spark that led to the start of barrel organ production in Steinkjer.

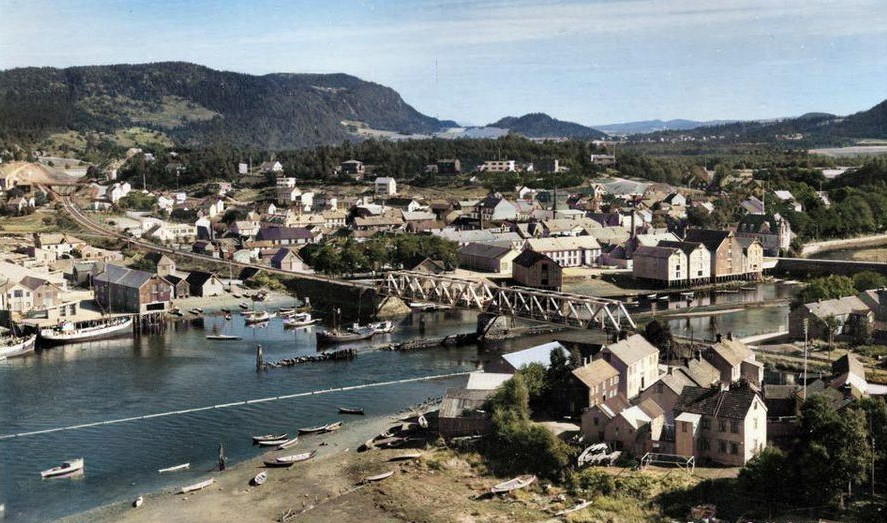

Steinkjer town centre after in 1905.Thomas made a barrel organ in Steinkjer just after 1850, having moved to Steinkjer in 1849. Early on he approached the Tharaldsen brothers who were professional braziers, to obtain parts for the organs he made. Both Tharaldsen brothers were skilled working with brass, a profession after their father. But they were also talented carpenters, a skill which laid a foundation which was to become central in the instrument production in the time to come. Positive number 20 from Tharaldsen was made in 1866, so it is valid to assume that Fosnæs and the Tharaldsen brothers came into contact only a few years after Fosnæs came to Steinkjer. Eventually, there was such a significant need for Steinkjerpositives that Christian also began to build barrel organs, in addition to Thomas.

Neither of the Tharaldsen brothers were musically gifted enough to pin the music to the barrels, and the production was so large that more hands were needed to contribute to that work. Jacob Schjefte was learning to play the violin from Fosnæs, and was introduced into the production that way. Until Jacob got involved in the production, it was Thomas alone who was in charge of the pinning job.

Theodor Bentzen was a well known-violin maker, and contact with Thomas Fosnæs was likely since they shared the same interest. The connection between Bentzen and the other builders is well documented, and his position as a positive maker is well known.

Jacob Schjefte collaborated early on with Ola Fjeldhaug, and helped Ola pin the music into the barrels of the positives he made. Ola was a crofter on Fjellhaugen under By, and he worked in the brick factory at By in the summer, and worked at his croft and forest in the winter. In his free time, Ola was often found in his workshop making furniture and building violins. This was the basis for the large scale collaboration for production of Steinkjerpositives, especially between Thomas, Christian, Jacob and Teodor. Christian and his brother Tørris built the mechanics and boxes, while Jacob and Teodor pinned the music to the barrels. The demand for barrels became so large that Ole Ramstad, Jacob's son-in-law, also pinned music from 1881 to 1883, a period of two years. Thomas, Christian, Jacob and Teodor built over 500 positives, with more than 400 positives in Christan Tharaldsen's name. This was over a quite long period, more than 50 years.

A portrait of an organ grinder, photo from Nordlandsmuseet's collections.Surviving positives signed by Jacob Schjefte do not look very different from the other Steinkjerpositives in Christian Tharaldsen's name. There are no known positives signed by Teodor Bentsen, but it's well known that he manufactured many of the barrels. The money they made from this work allowed them to buy the land they lived on. The organ manufacturing business provided enough income for them to leave being tenants and become landowners, Christian on his land at Fergeland and Teodor at Trana. Jacob resided in the city in today's urban area called "Påssåbyen" all his life.

The extent of production of Steinkjer positives from Ola Fjeldhaug is not known, but it is quite certain that there were several of them. Ola Fjeldhaug remained a tenant at Fjellhaugen throughout his life. Both Fosnæs and Tharaldsen were socially committed men who in many ways should be considered entrepreneurs of their time. Jacob Schjefte was also engaged in association work, and may belong to the same category. These three men attracted more builders in Steinkjer and the production surpassed more than 500 positives. This represents a significant amount of money, translated into current value it would be more than 10 million Norwegian kroner. This gave tenants an opportunity to become wealthy or to become landowners. It was in many ways an industrial fairytale for the people involved.

More than 14 men were building barrel organs in the area around Steinkjer.

Steinkjerpositives were also built in the villages around Steinkjer.

Breidesmoen, the home of the instrument maker Jacob Breidesmo in Snåsa.Other positive builders in the area around Steinkjer need to be mentioned, although it is not known if there was any cooperation between these and the builders in Steinkjer. Paul Olsen Landsem at Malm was an all-around handyman, and built barrel organs before emigrating to America in 1873. Neighbors in the same neighborhood, Peter and Odin Tverås were also known for being barrel organ builders although they were not able to pin the music to the barrels themselves. These three guys were neighbors, and they probably cooperated on that basis. Ole Ramstad was also originally from Tverås, and there may be a link there. It is assumed that Paul O. Landsem was acquainted with Thomas Fosnæs from his youth, and it is not impossible that Thomas influenced Paul to take up instrument building. Paul Landsem was known for his quick changes of profession, so it's not impossible.

Nils Lorntsen Opdahl, who lived not far away, was known for being able to make barrel organs and at the same time being able pin music to the barrels. It is both possible and probable that there was a collaboration among all four to complete the positives. Jacob Lorentz Bredesmo from Snåsa made several positives, one of which is in a museum at Snåsa, and another which has an exciting history of music with Christian content.

The shipping from Steinkjer was the foundation for the number and distribution of the positives.There was no market to sell a production of over 500 barrel organs in Steinkjer, or in the cities elsewhere at Innherred. However, the production took place at the same time as a very large production of windjammer sailing boat called Innherredjekt in the inner Trondheimsfjord and Beitstadfjord. The construction of over one thousand jekts with the whole of Norway as a market opened for large-scale export of Steinkjerpositives, especially northbound. The Jekt trade represented a sort of triangle trade with wood and timber north, which was exchanged for fish sold south as far as Bergen, with other goods from down there up to Trøndelag again. This gave the builders a trading channel and a relatively large market to operate. This allowed for such a large production of positives for so long a period for over 50 years.

The Music.

The music on the Steinkjerpositives is the traditional local tunes used by fiddlers in the Steinkjer district. It consisted mostly of round dance music, of which the waltz is a part. In addition we find the polka, reinlender and masurka. When the positives increased in popularity, there was a need of a larger repertoire. More music was needed and German popular dance tunes from the time were used. The Reinlender was present as early as 1866, while there are very few traditional "Pols" dances (not unlike the Swedish Hambo-Polska) pinned to the barrels.

The barrels are important in culture and music history because they are unique examples of "recorded" and preserved music from a time where all music merely was obediently handed over and memorized between musicians.

There were barrel organs which originated from Europe in the same period as the Steinkjerpositives were popular. These were often smaller positives, lightweight and portable, while the Steinkjerpositives, especially the two largest versions, was more or less regarded as portable organs. The Steinkjerpositives were well-built positives that lasted longer than the lighter positives from Italy or Germany. For that reason many have survived to the present day and the music is preserved. Around 1200 tunes have been recorded from various positives in Norway, from the just over 50-60 surviving Steinkjerpositives. 28 of these tunes were written down in book form by Charles Karlsen with help from Petter Andreas Røstad.

Popularisation in the seventies.

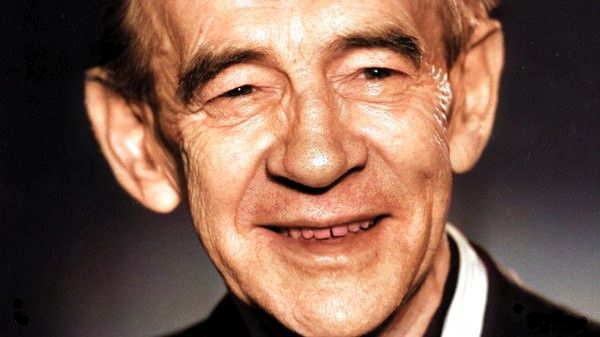

The Norwegian Broadcasting Company employee Otto Nielsen came to Steinkjer to make a program about the Steinkjerpositives. But there was nobody who could help to shed light on the history of the positives in Steinkjer. For this reason Charles Karlsen decided to study the phenomenon from the ground up. Charles Karlsen's acquisition of knowledge about the Steinkjerpositives together with Otto Nielsen's programs of the same topic led to great interest, and a rocketing value on the rather strange instruments, which eventually and ironically led to the fact that Charles could never afford to buy one for himself.

Otto Nielsen was keenly interested in the Steinkjerpositive. During a radio broadcast Otto interviewed an owner of a Steinkjerpositive - and discussed the price of it. The man who owned it wanted to have 15000 Norwegian kroner for his Steinkjerpositive - he needed that sum to to buy a new car. "I'll tell you one thing my good man", replied Otto Nielsen, "in the present day you will get many times 15000 for a Steinkjerpositive of good quality!"

Then the interest in the Steinkjerpositives totally exploded. Every owner of one ordered repairs to restore the positives they had. This event happened in the early 1970s, and tells something about our weakness for money - also in relation to culture. For what it was worth, this defined a good value for the positives, and they are now taken care of as valuable possessions.

Work which has been done to

document the history of the instruments.

Charles Karlsen started a large project to map the history of the Steinkjerpositives, and to map the surviving instruments. Jann-Magnar Fiskvik restored many of the old instruments and added valuable information to what ehave been learned already. In addition, both Bjørn Aleksander Bratberg and Åse Mørk researched the instruments and wrote theses about the Steinkjerpositives. Harald Sakshaug did some work to find the people behind the production of the instruments, what people they were, and what had to be added to the equation in order for such a large production to happen in the rather small town of Steinkjer. This digital museum is a collection of what information there is for a presentation of the Steinkjerpositives.